By Rick Scavetta

U.S. Army Garrison Stuttgart

Editor’s note: The Stuttgart Citizen newspaper has informed our community for nearly five decades. In 2021, Stuttgart Citizen will become a monthly magazine. To mark this transition, we are taking a look back. This is the first of two-part series on the impact the newspaper has had on our community.

During the summer of 1973, Spc. Mike Yurk got the orders he’d been hoping for – a transfer to Kelley Barracks to start work on a new community newspaper, the Stuttgart Citizen.

In high school, Yurk penned fishing columns for the Central Wisconsin newspaper and his school paper. Enlisting in 1972, Yurk qualified as an information specialist, based on news clippings and editors’ references. Assigned to the 223rd Aviation Battalion at Nellingen Kaserne, in Ostfildern, Yurk languished a year away.

Then, as the Army consolidated several Stuttgart-area garrisons into one U.S. military community, Yurk got his chance.

“They needed reporters, so I got yanked out of my unit and sent to the Stuttgart Citizen,” recalled Yurk, 71, during a recent interview from his home in Hudson, Wisconsin. “It was an exciting time. It was something new.”

Yurk’s beat included; covering swim meets and how-to articles on using public transit. He wrote a feature on Rothenburg ob der Tauber, one of the oldest cities in Germany that narrowly survived destruction in WWII. He wrote about nearby castles and included news on local restaurants, hoping that younger GI’s would follow his lead.

“It was an interesting time when I first got to Europe,” Yurk said.

Earlier that year, the Vietnam War ended. The Cold War with the Soviet Union was on. The East German border, with its watchtowers, minefields and razor wire, was 140 miles north of Stuttgart, then home to U.S. Army’s VII Corps at Kelley Barracks. U.S. European Command had moved from France to Stuttgart’s Patch Barracks just five years earlier.

Terrorism surfaced in Europe. A year earlier, Red Army Faction terrorists killed four Soldiers in bombings at Army posts in Frankfurt and Heidelberg. Members of the RAF, also known as the Baader-Meinhof gang, were later imprisoned in Stuttgart. Arab terrorists in Munich kidnapped and killed Israeli athletes during the 1972 Olympics.

After the October 1973 Arab-Israeli War, Arab oil producers embargoed petroleum causing a fuel shortage.

“OPEC started to shut off the oil in the winter of 1973,” Yurk said. “In Germany, they shut down all kinds of transportation. On Sunday, you couldn’t even drive. If you had duty, you had to get a special pass to show the police.”

Back then, the U.S. military had 20 posts and housing areas in the greater Stuttgart region. There were roughly 31,000 Soldiers, family members and Army civilians. Long gone are places like Pattonville near Kornwestheim and Flak Kaserne in Ludwigsburg.

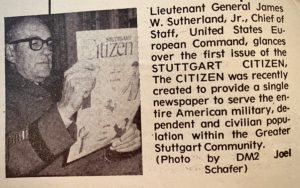

The Stuttgart Citizen began as an eight-page weekly, just as the Army consolidated its many posts in and around Stuttgart into one community. Lt. Gen. George Blanchard, VII Corps Commanding General, oversaw the consolidation. His top concerns; the quality of on-post schools, safety inspections for personally-owned vehicles and housing area renovations. Blanchard’s column led the first edition.

“It is unusual to find a community of over 20,000 people which is not served by a publication capable of disseminating news of interest and value to the local population,” said Blanchard, adding that the Citizen would “contain news and notices of wide interest to the residents of Stuttgart, tying the community together.”

The German Deutsche Mark was 3.25 to the dollar, so even a private could live well. Yurk lived off post in Stetten, near Stuttgart Army Air Field, with his wife and daughter. Some Soldiers, however, were sending their families home, because of increased costs and the devaluation of the dollar under the Nixon administration, Yurk said, adding that Blanchard wanted to create a community for service members.

“Gen. Blanchard took to heart taking care of the enlisted guy and pulling things together in Stuttgart and making it a community,” said Yurk, who once interviewed the general for the Citizen.

Important news and information in 1973 was not unlike what a community member might find today on Facebook, or the USAG Stuttgart App. A copy of the first edition – dated Dec. 3, 1973 – has become yellowed and tattered over the past five decades, but it remains as a piece of history in the garrison command building. A look inside reveals how some things changed, yet so much is the same.

That first issue ran the new shuttle bus schedule and had tips for winter driving. A set of four spiked tires cost $80 then at the Patch garage. Headlines also included the launch of the first local JROTC program, a new AFN Stuttgart call-in show for commanders to answer community questions, and the first German-American Boy Scout Jamboree at the Panzer training area. Army Community Service opened its first lending closet on Panzer Kaserne. Soldiers produced an anti-drug rock musical. Students visited the heavily guarded border with East Germany.

Jobs for family members were a hot topic. Local German companies were hiring. For five German marks (less than $2) per hour, spouses could work off post wiring small electrical fixtures in Kornwestheim, or at a cafeteria in Feurbach.

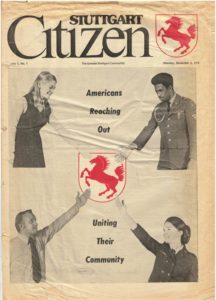

A story on “no driving Sunday,” an effort imposed in Stuttgart to economize fuel consumption during the oil embargo explained how Americans on post were limited to 40 liters per fill-up and warned that no outside electric Christmas decorations were allowed. The newspaper ran a contest for community members to come up with a motto. Lt. Col. Donald Wuerz, with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, beat 126 other submissions and won a $25 savings bond for his entry, “American Partners for a Better Stuttgart.”

“People are unaccustomed to, and in fact, surprised by an overseas city-wide newspaper for the community,” read an early announcement. “The Stuttgart Citizen is your newspaper, the contents rely heavily on your contributions. We’re interested in anything and everything happening within the community.”

Another story was about a lost statue of a European bison, the emblem of the German Army’s 7th Panzer Regiment that once stood at Patch Barracks. As the story goes, the missing buffalo was damaged during WWII then allegedly dumped in a bomb crater and plowed over. Or maybe it’s below an apartment building in the housing area.

In January 1974, the Army issued the first washers and dryers to on-post residents. Yurk’s editor, Master Sgt. Roy Bonham, was a building coordinator and posed many tough questions to the junior reporter. “Who’s responsible for them? Who’s signing for them?” Bonham asked Yurk. “I rewrote that story four or five times,” Yurk said. “That was a huge, huge deal, it was the first time they had done anything like that.”

Yurk’s final Citizen series focused on the military police. He spent nights on MP patrols, shadowing investigators and chatting with the MP desk sergeants. He wrote about an inebriated Army cook who jumped from a moving car on the highway, then being evacuated by helicopter to the Army hospital in Landstuhl and a distraught Army spouse arriving at the Robinson Barracks’ MP station, because German police jailed her teenage son for trafficking hashish.

Yurk continued to write about the outdoors and fishing by sinking stories into a monthly newsletter at the Patch Rod and Gun Club. In mid-1974, Yurk, his wife and two young children moved to Fort Leonard Wood, where he joined the post newspaper. Later, Yurk attended the University of Wisconsin and earned a commission in the military police corps. Back on active duty in Nürnberg, Yurk’s MP company trained in Böblingen – where he last read the Citizen, the newspaper he helped start.

Retiring as a major in 1994, Yurk never stopped writing. He went on to publish more than a dozen books and write fishing columns for Wisconsin newspapers. Visiting each year in Key West, where the newspaper is also named the Citizen, Yurk catches himself calling it the Stuttgart Citizen.

“The thing I loved to do was write. That started when I was in high school,” Yurk said. “But, I really enjoyed being in the Army. It was something bigger than you. It gave me all the things I ever wanted – fun, travel, adventure and a family. I look back at those years very fondly.”