Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the September 2021 issue of the Stuttgart Citizen magazine.

By Bardia Khajenoori

USAG Stuttgart Public Affairs

Seventy-five years ago this month, Stuttgart played host to a speech that redefined U.S. policy toward occupied post-World War II Germany and set the framework for the future German-American partnership.

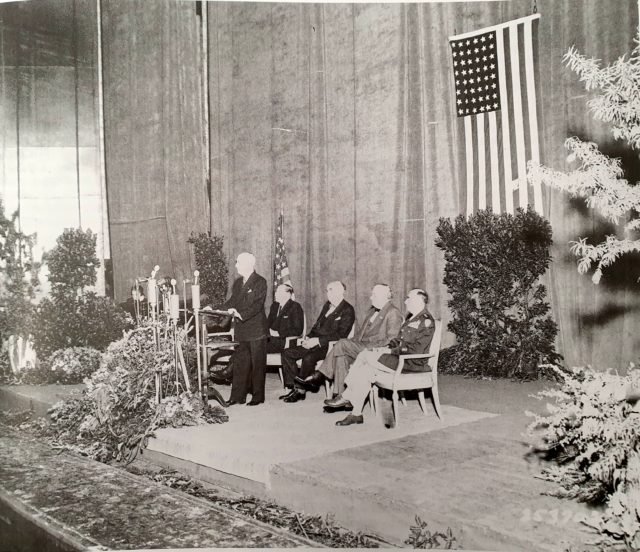

Then-U.S. Secretary of State James F. Byrnes presented the “Restatement of Policy on Germany” on September 6, 1946 at Stuttgart’s opera house — the only venue in the heavily bombed city capable of hosting such a large audience.

His address would come to be known as the “Speech of Hope,” where he offered Washington’s support for the country’s economic and political reconstruction and promised long-term American engagement.

“We will not shirk our duty,” Byrnes said in the speech. “We are not withdrawing. We are staying here.”

This commitment represented an effective change of policy, both in terms of the expected duration of the American post-World War II mission, and the U.S. perspective on how rebuilding should be undertaken.

It established a contrast with the relatively swift withdrawal of American troops from Europe after World War I, and at the same time, set forth a different path from the plan offered by U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr., which would have seen Germany de-industrialize and revert to a primarily agricultural country.

“The Speech of Hope was important to the U.S. side and the Allies because it was a clear statement by the U.S. Secretary of State on what the U.S. policy toward Germany was, and that as long as there was an occupying force that we would be here to be a part of it,” said T. Sean Schulze, U.S. Forces Liaison Officer for Baden-Württemberg and Thuringia.

“And from a German standpoint, it was important because it indicated that there was a light at the end of the tunnel — that the U.S. intended to follow through on the stated intent to permit, and even enable, Germany to rebuild civil government on its own authority and for Germans to govern themselves,” Schulze said.

Indeed, Byrnes’s words were well-received by the Ministers-President of the three states in the American occupation zone, who responded with a joint statement: “What he elaborated in this speech… has given us new courage and new impetus for the difficult and responsible reconstruction work in which we are engaged.”

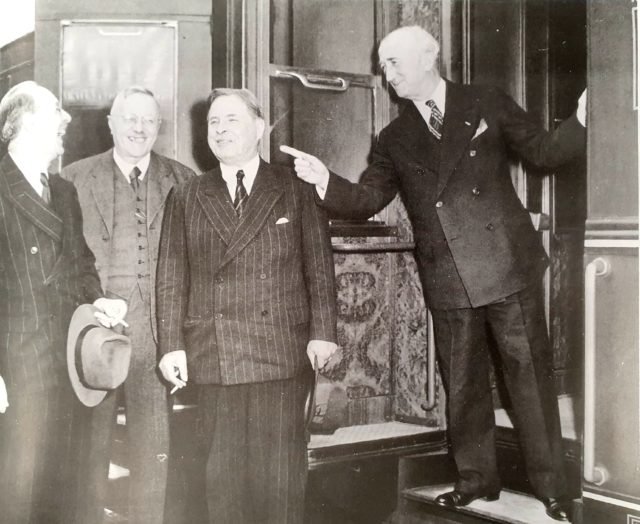

The architect of Byrnes policies was General Lucius D. Clay, military governor of the U.S. occupation zone in Germany. Clay was tasked with forming a response to the address by Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov in Paris two months earlier, in which he had suggested a unified, democratic country.

In truth, the devil was in the details.

“It was clear to pretty much anybody who was listening that he was really talking about a communist or Soviet-style democracy, and not democracy as it would be understood in the West,” said Schulze. Byrnes’s response “put up a challenge to that Soviet concept of the way ahead.” It also sought to resolve other disagreements between the Allies on management of the occupation.

“For Germany, ‘the Speech of Hope’ laid the foundation for setting up our liberal-democratic fundamental order, for our western ties, our economic structure and for the longest lasting peace in our history,” said Erwin Teufel, Minister President of Baden-Württemberg on the occasion of the speech’s 50th anniversary in 1996.

“We do not consider this day a mere symbolic, historical date, but a commitment for today and for the future.”

Teufel added that he was “pleased” at the continued presence of U.S. forces in Baden-Württemberg: “No longer as occupiers, but as partners and friends.”