John Reese

USAG Stuttgart Public Affairs Office

On a chilly winter night, the future lives of two young Sailors, separated half a world away and then unknown to each other, became intertwined when tragedy struck in a Spanish port, Jan. 17, 1977.

Forty years later, the shipmates journeyed from their civilian duty stations at U.S. Army Garrison Stuttgart’s Panzer Kaserne to remember the 49 Sailors and Marines who lost their lives when a freighter collided with an LCM-6 “Mike” boat (landing craft-medium) returning them from a liberty call.

Kerry Dauphinee, coordinator, Exceptional Family Member Program, and Joe Holder, School Liaison Officer, both of USAG Stuttgart and both Navy veterans, joined survivors, rescuers, Gold Star family members, and Spanish and American officials in Barcelona, Spain, in remembrance of those lost that winter night four decades ago, Jan. 17, 2017.

Ships Serviceman 2nd class Dauphinee, 24, was on a long voyage. His ship, the USS Guam (LPH 9), a helicopter amphibious assault ship with a crew of 708 and a Marine compliment of 1,750, had visited Mombasa, Kenya, spent Christmas in Egypt at the Pyramids, transited the Suez Canal, participated in an exercise off coast of Greece and made a port call at Naples, Italy, before arriving at Barcelona. He, his bunkmate, 19-year-old Michael Sims and his petty officer went ashore to enjoy the hospitality of the Spanish port.

That evening, Dauphinee’s petty officer suffered a heart attack while ashore. Dauphinee escorted the sick man back to the fleet landing to board the next-to-last run of the Mike boat and brought him to the sickbay aboard the Guam.

Around 2 a.m., the low-profile amphibious assault landing craft in service as a liberty boat was carrying 124 Sailors and Marines to their home ships, the Guam and the USS Trenton (LPD-14), in its open cargo bay back. The ships were anchored more than a mile offshore, outside of the harbor. It was the last ride home of the night; to miss it would’ve been to miss roll-call the next morning.

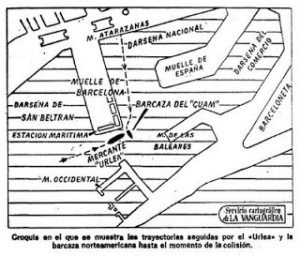

The boat rounded a high commercial pier straight into the path of the 480 ton Spanish freighter Urlea. There was no time to react — the much larger freighter rammed the crowded Mike boat, striking it twice and causing it to capsize. The impact threw many of the passengers into the cold water of the harbor. Some of the Sailors and Marines were killed outright in the collision. Some were trapped in air pockets in the overturned ship. Others climbed atop the exposed hull and some were able to swim to shore 80 feet away.

“Shortly after the accident, at 2 a.m., the Guam sounded collision alarm,” Dauphinee said. “Normally, a collision alarm included an announcement of the frame number to minimize casualties.”

But there was no announcement and both ships mustered to account for all personnel.

“The word just got around quick that the Mike boat got hit,” Dauphinee explained. “In the Navy we call it muster, and we had to keep on mustering because they hadn’t recovered everybody.”

Rescue efforts began immediately. The Guam and Trenton sent rescue and assistance details. Spanish and American divers went into the 40-degree water to search for survivors.

Communication wasn’t good due to language differences, Holder said, but the divers from both countries saw there were survivors trapped below, holding on to a bar in an air pocket, and that they were running out of air.

“They were in the water for several hours, trapped underneath there, so the divers released air into the space,” Holder said. “Whatever light there was came from the divers, otherwise, it was pitch black.

After rescuing the living, it soon became apparent that it had become a recovery operation, as so many personnel had been killed. Twenty-five personnel from the Guam and 24 from Trenton had perished, the breakdown being 25 Sailors and 24 Marines.

Dauphinee’s bunkmate, Sims, was one of the casualties.

“There was a strong likelihood that my supervisor and I would’ve been on the boat that got hit,” Dauphinee said.

The 40th anniversary memorial took place at the site of the accident. Guam shipmate Lamar Thomas and his wife, Lisa, coordinated the event with Holder from their home in Amarillo, Texas, and were among the attendees. Six of the divers, including the Spanish divers who helped with the rescue and recovery, as well as the crane operator who helped raise the LCM,and a number of Gold Star family members attended the memorial at the port’s Royal Nautical Club.

“One shipmate walked into the room and said ‘Kerry, I remember you.’ It blew me away,” Dauphinee said. “Forty years, and this guy said ‘you haven’t changed a bit.’”

One shipmate still had the jacket he was wearing that night.

Lt. Col. David F. Lawrence, Marine attaché, Spain, came from his station in Madrid along with six Marines (two from the embassy and four from Quantico, Va., in country for a regular consulate security assessment). The Marines voluntarily brought their dress uniforms to form a color guard for the ceremony. Typically, they wouldn’t bring their dress uniforms for a security assessment, Holder said.

Two of Dauphinee’s shipmates from the Guam met at the ceremony for the first time; they hadn’t known each other during the time they served together on the ship.

“They became lifelong brothers. They had a shared experience,” Dauphinee said. “We were on the boat just an hour prior.

“One of the shipmates who attended passed away a week to the day after the ceremony,” Dauphinee said. “Another shipmate who went into the water helping with the rescue got hypothermia, suffered a heart attack and died 52 hours after the accident.”

Dauphinee spoke at the event and Holder, representing the Veterans of Foreign Wars, European Chapter, Post 10810, acted as chaplain. Holder and past VFW Europe department chief of staff, master of ceremonies Tony Millett from Nurnberg, went down early to coordinate at the event.

“We did a two-bell ceremony for the remembrance of fallen. It’s a Navy tradition,” Holder explained. “The colonel would say the name of the Marine, and Kerry would say the name of the Sailor, and after they named the ship they were from, I gave two rings on the bell.”

“And if their loved one was there, they’d stand up in silence for recognition,” Dauphinee added.

Emotions ran high, and even the lieutenant colonel hesitated after a name was called, Holder said.

Holder noted it was the first time that many of the Gold Star family members witnessed force protection measures taken before the memorial.

“It gave them a better sense of what the men and women stationed overseas go through on a daily basis for operational security and force protection,” he said.

Although he was stationed on Okinawa at the time of the accident and didn’t meet Dauphinee until years later, Holder and his shipmates in the Pacific were operating the same class of Mike boats. Holder was scheduled to land Marines in amphibious training using an LCM-6.

“Specific safety rules and regulations, the number of personnel aboard … the Navy changed operations,” Holder said. “Those Sailors and Marines didn’t die and nothing changed from it — that’s not true. Things did change.”

Dauphinee still has powerful memories from the accident. That night taught him that he and his shipmates weren’t indestructible.

“One of the things I’ve thought of over the years was ‘what were the people on the pier doing?’ And what I found was the people there tried to help out with the rescue as much as possible,” he said. “It hasn’t been until recently that I’ve been able to come to terms.”

At the remembrance, one of the Spanish divers spoke through an interpreter.

“He said never before or since has anything ever impacted him as much as this one rescue. ‘I want to thank you for making me young again,’’” Dauphinee said.

A 45th year remembrance is already in the planning.

(Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the February 9th newsstand edition of the Stuttgart Citizen. It is posted online for the first time in recognition of Memorial Day, May 29, 2017.)